Deion Luwynn Sanders. Neon Deion. Prime Time. Leon Sandcastle. Coach Prime. Whether you know him as the polarizing off-field personality, electric on-field shutdown corner, or fun-loving mentor and coach, there is no diminishing the legacy Sanders has blazed during his 54 years of life. But there is more to Deion Sanders than is seen on camera.

Deion Sanders: Beyond the glory

Across 14 NFL seasons, 188 games, and five franchises, there wasn’t much Sanders didn’t accomplish. He earned eight Pro Bowl invites and six first-team All-Pro selections. He was the 1994 Defensive Player of the Year and a two-time Super Bowl champion.

After retiring (a second time) in 2005, Sanders was enshrined into the Pro Football Hall of Fame a mere six years later. Not to mention he is the only athlete to appear in a Super Bowl and a World Series. But in his prime and reaching the pinnacle of success never before achieved, something was missing. And on one fateful night in 1997, the glass house Sanders called home finally shattered.

Sanders’ upbringing is unfortunately not uncommon. His parents divorced when he was only two years old, leaving his mother (Connie Knight) to raise him and his sister in a public housing project in Fort Myers, Florida.

It was Sanders’ mother who worked as a cook and custodian at the local hospital to make ends meet. A young Sanders internalized that work ethic, and as we will soon see, it ultimately helped him reach heights never before seen. His father was also in the neighborhood, but he was poisoned by drug addiction and consequently unemployment. A stepfather figure would soon enter Sanders’ life, but he too had his own addiction: alcohol.

To avoid her son falling into bad habits and the wrong crowds, Sanders’ mother signed him up for sports at a young age. It started with baseball, although football would follow shortly thereafter.

Sanders’ mother and stepfather couldn’t attend games due to work. And even though his biological father would occasionally be in the stands, he did so to bet on the games. It was on the Pop Warner and Little League fields that Sanders learned to play for himself and his team, not for others.

On top of playing sports, Sanders developed his entrepreneurship at a young age. He cut lawns and developed a business at the Fort Myers Royals’ stadium (the minor league affiliate of the Kansas City Royals). He would run around for home run balls that landed in the stands and sell them to fans looking for a souvenir.

Sanders chooses Florida State over MLB opportunity

Fast forward a few years, and Sanders’ athleticism began to shine. He starred on the baseball, football, and basketball teams at North Fort Myers High School. And it was on the hardwood where Sanders would first receive the bigger-than-life nickname many now know him by — “Prime Time.” Once Sanders realized a professional sports career was in his grasp, he promised his mother he would make enough money to ensure she never had to work another day in her life.

Graduating from Fort Myers as an all-state honoree in each sport he played, Sanders was at a crossroads. Florida State offered him a full-ride scholarship to play football for their program. Meanwhile, the Kansas City Royals selected Sanders in the sixth round of the 1985 MLB Draft, bringing his childhood full circle.

Ultimately, Sanders bet on himself and the prospect of making millions in the NFL, driving to FSU’s campus with “Prime Time” written on his license plate. It didn’t take long for the Seminoles to feel his impact. He recorded a pick-six and a punt return touchdown on the gridiron, played outfield for the fifth-ranked baseball team in the nation, and aided the track and field team to a conference championship.

Becoming Prime Time

At this point, an agent sat down with Sanders and explained the NFL salary for defensive backs (one of the lowest-paid positions in the sport at the time). But that wouldn’t do for Sanders, as he had a promise to keep with his mother.

His solution? Build a brand around a flamboyant public personality that “love him or hate him, you want to see him play.” However, Sanders didn’t know that, like his father and stepfather before him, he too would soon have an affliction. And like drugs and alcohol, it was addicting and self-imposed. The only difference was that Sanders created his substance and even named it — “Prime Time.”

Sanders tore a page out of corporate marketing books and created an image he knew would sell. He took inspiration from Muhammad Ali (brashness), Hank Aaron (mental fortitude), O.J. Simpson (character), and Julius “Dr. J” Erving (professionalism). Brian Bosworth’s media explosion at Oklahoma also added fuel to the fire and proved the concept could work. Yet, Prime Time would become a national icon because he had the game to back up his bravado, practicing to dominate, not just win.

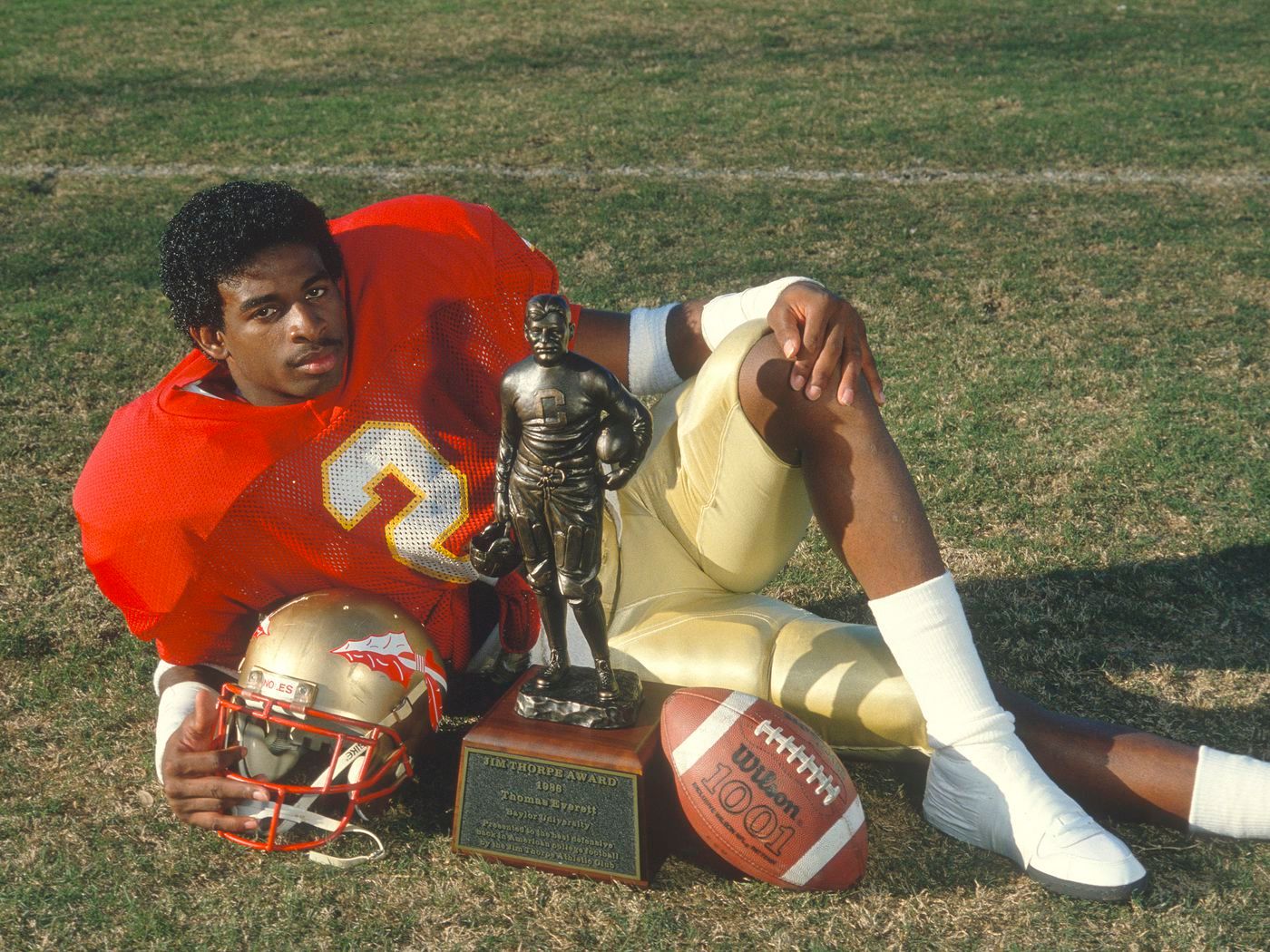

Under legendary head coach Bobby Bowden and the tutelage of defensive coordinator Mickey Andrews, Sanders left FSU as a two-time consensus All-American CB. In his final collegiate campaign in 1988, he received the Jim Thorpe Award and capped the season off the only way he knew how.

Against Auburn in the Sugar Bowl, Sanders snatched the game-sealing interception, bringing his career total to 14 INTs and three pick-sixes. But Prime Time was also electric as a punt returner. He broke the school’s career punt return yards record with 1,429 and notched three touchdowns.

In an interview last year, Andrews said Sanders “was relentless in the pursuit of his development.” Additionally, Bowden stated he was his “measuring stick for athletic ability,” and Florida State retired his No. 2 jersey in 1995.

On the diamond, Sanders made a name for himself stealing bases (27 as a junior). On May 16, 1987, the Metro Conference baseball and track championships were played simultaneously in Columbia, South Carolina. Subsequently, Sanders had to play in the conference semifinal baseball game, run a leg of the 4×100 relay, and suit up for the baseball championship (which they won) — a microcosm of his unbelievable athletic gifts.

Professional stardom

As a junior in college, the New York Yankees selected Sanders in the 30th round and paid him $75,000 to play on their minor league baseball team. That was the minors, and as Sanders often quotes, “we focus on the major, not the minor.” He made his MLB debut in May of 1989, just one month before the Atlanta Falcons would select him fifth overall in the NFL draft.

Sanders expected to go that high, even spurning the New York Giants (who were picking at No. 18) when they asked him to conduct a written test in the pre-draft process.

“I’ll be gone before (your pick),” Sanders told the team. “I’ll see y’all later. I ain’t got time for this.”

Shortly after signing his first NFL contract, Sanders delivered on his promise to his mother, buying her a new home on the wealthy side of town in Fort Myers.

In the first game of the NFL season, the Falcons hosted the Los Angeles Rams. The Atlanta crowd wanted to see the fifth overall pick prove his worth. Of course, it didn’t take long before he did just that.

Sanders fumbled and recovered his first punt return and bobbled his second. But that second attempt gave the fans what they wanted. Sanders picked the ball off the ground, ran backward 10 yards, broke multiple tackles, and high-stepped his way into the endzone.

During the 1989 season, Sanders became the first player to hit a home run and score a touchdown in the same week. And if you thought his Prime Time persona was just for football, you’re mistaken. Facing off against the Chicago White Sox, Sanders stepped to the plate and drew a money sign in the dirt with his bat, causing an altercation between the two sides.

Prime Time was a controversial figure, with more “traditional” media members and fans criticizing his animated personality and flashy style.

One of Sanders’ biggest detractors was well-known baseball analyst Tim McCarver. He ripped Sanders on live TV for the “selfish” act of playing two sports while with the Falcons and Atlanta Braves. When the Braves won the National League Championship in 1992, Sanders sought out McCarver in the locker room, dumping a bucket of ice water over him as he conducted an interview. As Sanders said in a made-for-TV documentary in 2002, “[McCarver] needed to be cooled off a little bit.”

Sanders’ career took off as quickly as his 4.29 40-yard dash. He raked in money from two professional sports contracts as well as through countless endorsement deals. Prime Time and his first wife and college sweetheart Carolyn Chambers also welcomed their first two children into the world in 1992 (Deiondra) and 1993 (Deion Jr.). He became good friends with multiple pop culture stars, including Snoop Dogg, MC Hammer, and Ice Cube. And in 1994, he released his first and only album “Prime Time,” featuring the single “Must Be the Money.”

So it’s fair to say life was, on the surface, good for Sanders. Things only got “better” when he won back-to-back Super Bowls with the San Francisco 49ers (1995) and Dallas Cowboys (1996) a couple of years later. However, the inner demons lurking in the shadows of Sanders’ life weren’t in the shadows anymore.

Sanders crashes into a newfound faith

There was trouble in paradise, and everything Sanders built started to crumble.

You see, Sanders never cared about the accolades. He never cared about the media attention. Football and baseball were games he played and appreciated for the platform and financial stability they gave him. But Sanders could never love something that couldn’t love him back. And when he reached the top of the mountain and realized happiness wasn’t waiting for him, an internal struggle commenced.

Following his first Super Bowl with the 49ers, Sanders explained, “I was the first one out of the locker room, the first one home, the first one to bed. And I said, ‘this wasn’t what I thought it was. I’m not even happy.'”

While he learned to tune out the media spotlight and the fans in the stands, no one truly knew Sanders. They only knew Prime Time, and spending so many years wearing a mask of such magnitude weighed on him. In fact, Prime Time was slowly killing the Deion Sanders that those who genuinely knew him loved. His marriage faltered, and he would eventually divorce Chambers and lose custody of his two oldest children.

“I was going through the trials and tribulations of life — I was pretty much running on fumes,” Sanders said. “I was empty, no peace, no joy. Losing hope with the progression of everything.”

Sanders realized he was on the same trajectory as his father, who had passed away in 1995. He would be in the same area as his kids but watch them from afar. Feeling like a failure as a husband and father set Sanders spiraling to depths few bounce back from.

About 30-40 feet at the bottom of an embankment near the Ohio/Kentucky border laid Sanders in his Mercedes. It wasn’t his time yet; he had far more to give the world. But he didn’t believe that in May of 1997.

Sanders called his agent Eugene Parker and told him to come to his apartment. But when Parker made the 100-mile trip from Indianapolis, Indiana, to Cincinnati, Ohio, he didn’t find Sanders. Instead, he found a suicide note detailing his last wishes.

According to Sanders, divine intervention saved his life in the crash. And days later, he would drop to his knees and surrender himself to a higher power. As he established his faith, he began to separate the personality that was Prime Time and the person that was Deion Sanders.

The rise of Coach Prime

After his playing career and a stint as a media analyst, Sanders’ faith placed him in a more fulfilling profession: coaching. When people think of elite athletes, they don’t typically think of the limitless hours of practice and tape study off the field. Sanders was a true student of the game. So much so that despite being a shutdown corner as a player, he coached the offensive side of the ball.

He was the head coach at Prime Prep Academy (2013-2015) and Triple A Academy (2015-2017) before joining Trinity Christian High School as an offensive coordinator until 2020. Sanders loved coaching at the high school level, but an opportunity arose where he could make an even bigger difference.

On Sept. 21, 2020, the Jackson State Tigers announced Sanders as their 21st head coach in program history. JSU is a historically black college or university (HBCU) on the FCS level and plays in the Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC), which is entirely made up of HBCUs.

COVID-19 delayed SWAC competition until the spring of 2021. But in an abbreviated season, JSU went 4-3, and Sanders learned valuable lessons as a collegiate head coach. He filled his staff with former NFL players and coaches and used his connections to bolster the Tigers’ football program.

Additionally, he secured the services of multiple players transferring out of Power Five schools. But Sanders’ aim wasn’t just to return JSU to the summit of HBCU football.

In an interview last summer, Sanders said he believes he was called to Jackson State to “level the playing field, challenge the status quo, bring resources, expose things that need to be exposed, and give these kids the attention, love, and compassion they need.”

Sanders not just focused on wins, but on making a difference

Last year, the Tigers took the conference by storm, producing a program-record 11 wins. Thus, Sanders earned the Eddie Robinson Award, given to the top FCS head coach. With his platform, he not only brought eyes to Jackson State but all HBCUs in the SWAC and other conferences. ESPN broadcasted HBCU games. Media outlets wrote articles shining a light on the culture. And the attention paid off.

Infamously, zero HBCU players were selected in the 2021 NFL Draft. But in 2022? Four HBCU athletes heard their names called, with more signing as undrafted free agents.

Sanders’ impact stretched to the recruiting trail as well. Jackson State flipped the recruitment of the top prospect in the 2022 class, defensive back Travis Hunter. Ironically, Hunter initially committed to Sanders’ alma mater: Florida State. Many regarded the move as one of — if not the — most significant signing day moment in college football history.

JSU received a hard commitment from four-star WR Kevin Coleman not long after. And there are sure to be more four and five-star recruits taking HBCUs more seriously in the coming cycles.

Moreover, in the era of NIL deals and college players finally being paid for their talent, who better to prepare these young men than Prime Time himself? He knows how to build a brand, market said brand, and manage finances at that age better than most head coaches in the country.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg for Sanders. His purpose is to create widespread change — not just at JSU but for all HBCUs. And not just for the players but also for the coaches and staff members within the programs.

How will he achieve the change he seeks? Bringing in top-flight recruits and installing new locker rooms and fields is great. But increasing exposure, enrollment, and creating professionals both on and off the field is how you leave an indelible effect.

Coach Prime plastered “I Believe” all over his and Jackson State’s social media accounts, as well as in the team’s facilities. It’s not just a belief in faith, but a belief in yourself and those around you. As Sanders explained, “If you don’t believe in yourself, nobody else will either.”

As a player, Sanders always delivered the on-field success to back up the expectations levied by his on-camera persona. But now, he doesn’t need Prime Time. Coach Prime is the person Sanders needed when he was younger. And while he can’t change the past, he can be a navigation system for every young man and woman that walks through his door at Jackson State.

Guided by his spirituality, Sanders is primed to succeed yet again. Only this time, he doesn’t need a mask to amplify his voice — people just listen.